The region we now call Southeast Asia was once referred to as Indo-China–so named by the west because the countries ringing the Golden Triangle displayed the influences of both India and China. Although the term “Golden Triangle” often refers to opium production, in this case it means exotic curries

The “Return of the Oil”

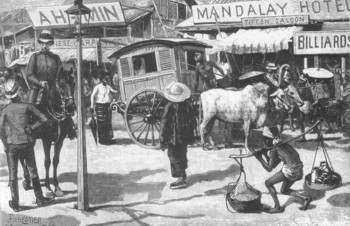

Burma (now called Myanmar) has more than a hundred distinct ethnic groups, but Burmese cuisine has mostly been influenced by the cooking styles of India, Thailand, Cambodia, and China–the homes of most of the original immigrants. Tibetan people arrived in Burma in the ninth century A.D., and the Mongol Dynasty from China conquered the region in 1272, so the Chinese influence on cooking is significant. However, since the very first settlers of Burma were the Sakya warriors who migrated from India and settled at Tagung about 250 B.C., it is not surprising that curries play an important role in the cuisine.

Burmese cuisine is a culinary treasure; the dishes are easy to prepare and offer delightful challenges to adventurous cooks. The Burmese often quote a proverb: “You cannot meditate on an empty stomach” to explain their love of good food. The cooking of the country, like that of any other nation, has regional variations. The Shaan people, from neighboring China, use the least amount of spices and use soy sauce instead of fish sauce. The people bordering Thailand make their curries more soupy, and those in the southern region enjoy spicier curries.

According to my friend Richard Sterling, who has reported on Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos as a contributing editor, “The Burmese cook approaches curry in a way as constant as the ancient past or the monsoon cycle.” During his extensive visits to Burma, Richard watched many curries being prepared. First, the Burmese make a curry paste out of their five basic ingredients: onions, garlic, chiles, ginger, and turmeric.

Some Burmese cooks use other other spices as well, including an occasional prepared curry powder. But the hallmark of the Burmese curry is its oiliness. The cooks use a combination of peanut oil and sesame oil, about a cup of each in a wok, and heat it until it smokes–this is called “cooking the oil.” The curry paste is added, the heat is reduced, and the paste is cooked for fifteen minutes. Then meat is added, cooked, and eventually the oil rises to the top. This state is called see byan, “the return of the oil.” When the oil floats on top, the dish is done. The oil is not skimmed off the top, but rather is absorbed by the side dish of rice when it is served.

Fiery Pastes and Carved Fruits

In neighboring Thailand, the people believe that they had more time to evolve their unique cooking because they were smart enough to keep would-be foreign invaders at bay. Thailand is the only Asian country that was not subjected to European rulers; it was rarely overrun by its Asian neighbors, and it has seen relatively very few wars. These unique conditions gave the Thai kings time to spend with their queens and mistresses, to hire the best cooks, and to encourage the cooks to create new dishes and improve the traditional ones.

The Thai curries are extensively spiced with chiles. Contrary to popular belief, there is not just one “Thai chile,” but rather dozens of varieties used in cooking. When I toured the wholesale market in Bangkok in 1991, I found literally tons of both fresh dried chiles in baskets and in huge bales five feet tall. They ranged in size from piquin-like, thin pods barely an inch long to yellow and red pods about four inches long. When making substitutions, cooks should remember that, generally speaking, the smaller a chile, the hotter it is. At left, prik chee fah chiles in Bangkok.

It is the fresh chiles that are ground up with other ingredients to make the famous Thai curry pastes, but rehydrated dried chile can be substitued in a pinch. Two key curry pastes are the heart of Thai cooking; a red curry paste, called nam prik gaeng ped, uses red chiles, lemon grass, galangal and a number of herbs. The green curry paste is made with small green Thai chiles, but serranos make a good substitute. It looks deceptively mild, like a Mediterranean pesto, but it very hot indeed. These pastes are easily made fresh, keep well for at least a month in the refrigerator, and add a terrific zing to curries, but some very tasty commercial curry pastes are available in Asian markets. A yellow curry paste, colored with ground turmeric, is perhaps the mildest among all Thai pastes.

A visitor to a Thai home or restaurant is won over not only by the aromatic food but also the elegant way it is served. Commonly accompanying Thai curries are elaborately carved fruits and vegetables, which often resemble large flowers. Rosemary Brissenden, author of Joys and Subtleties: Southeast Asian Cooking, described the art: “Fruit and vegetable carving is traditionally a highly cultivated art. Anyone who has watched the infinite calm of a Thai woman carving a piece of young ginger into the likeness of a crab with its pincers at ready will bear witness to this. Thai salads are also artistically arranged, and food historians believe that such elaboration dates back to the days of royal culinary competitions, when the dishes had to look as spectacular as they tasted.

Of Lemongrass, Galangal, Giant Catfish, and Frog Legs

While the foods of Thailand have been covered with increasing frequency in books and magazine articles, and articles and books appear on Burmese and Vietnamese cuisines occasionally, hardly any information is available on Cambodian and Laotian foods. This is one of the unfortunate results of warfare and unstable political situations in the two countries. Again, I have depended on Richard Sterling for most of our information on Cambodian and Laotian curries. He was brave enough to travel to these countries in the early ’90s collect some curry recipes for me.

In Cambodia, which is now called Kampuchea, the Khmer cooks depend on chiles, lemongrass, galangal, and fish sauces in most of their curries. Galangal, at left, is an Asian relative of ginger. “The Cambodians are great eaters,” Richard told me. “Their calendar is full of historical feasts, and any gaps are filled by weddings, births, funerals, and auspicious alignments of the stars. Theirs is a land of abundance. They enjoy regular harvests of rice, wild and cultivated fruits, fresh and saltwater fish, domesticated animals, and fowl and game. They love to eat meat. Pork is the most popular and it is excellent, as are all the meats. An English journalist I dined with said of her beefsteak that it was the best she ever had. I didn’t tell her it was luc lac, or water buffalo.”

Richard adds, “In Cambodia, as in India, there are as many curries as there are cooks. But all true Khmer curries have five constants: lemongrass, garlic, galangal, and coconut milk; the fifth constant is the cooking technique, dictated by the texture of lemongrass and the consistency of coconut milk.”

In nearby Laos, two distinctive styles have emerged. One is that of the Laotians, whose cuisine is very similar to that of the Thais except that lemongrass and galangal are only rarely used in their curries. The other cooking style is that of the Hmong, a tribal people of southern Chinese origin. The Hmong cuisine, naturally, was inspired more by the Chinese, so soy sauce replaces fish sauces. Shallots, ginger, and chiles are also common in Laotian curries. All of the ingredients are pounded together in a mortar until they are very smooth, and then are cooked in coconut milk until a silky sauce is formed.

“A good Laotian curry sauce is similar to the consistency of hollandaise,” says Richard. Meats and fish are commonly curried in Laos, but not vegetables, which are eaten on the side. Of particular interest are the huge Asian catfish found in the rivers of Golden Triangle countries, seen at left.

One of the most interesting Vietnamese curries Richard found combines frog legs and cellophane noodles; this was understandably one of the curries beloved by the French, who occupied Vietnam between 1858 and 1954, except for the Japanese conquest during World War II. For this article, I suggest Vietnamese Chicken Curry, but you can substitute skinned and cleaned frog legs-especially from extra-large bullfrogs-for the chicken. The following recipes are fun to try, but the cook should not limit the meal to the cuisine of just one region. While the curries are cooking, remember the Burmese saying: “Eat hot curry, drink hot soup, burn your lips, and remember my dinner.”

Thai Red Curry Paste (Nam Prik Gaeng Ped)

A popular ingredient in Thailand, this curry paste can be added to any dish to enhance its flavor. It is, of course, a primary ingredient in many of the famous Thai curries. Traditionally, it is patiently pounded by hand with a heavy mortar and pestle, but a food processor does the job quickly and efficiently. It will keep in the refrigerator for about a month. Marinate a dozen shrimp in this paste, stir fry them quickly with the paste in canola oil, and the result is an instant lunch or dinner.

Ingredients

- 10 small dried red chiles, such as piquins, stems removed

- 2 teaspoons ground cumin

- 2 teaspoons ground coriander

- 2 small onions

- 1 teaspoon black peppercorns

- 1/2 cup fresh cilantro

- 1/4 cup fresh basil or mint leaves

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 3 2-inch stalks lemongrass, including the bulb

- 1 1-inch piece of galangal, peeled

- 1 tablespoon chopped garlic

- 1 tablespoon shrimp paste

- 1 tablespoon corn or peanut oil

- 1 tablespoon lime zest

- 1/4 cup water

Instructions

- Soak the chiles in water for 20 minutes to soften, then remove and drain. Roast the coriander and cumin seeds for about 2 minutes in a dry skillet, and when they are cooled, grind to a fine powder in a spice mill.

- Combine all ingredients in a food processor or blender and puree into a fine paste. Store it in a tightly sealed jar in the refrigerator.

Yield: About 1 cup

Heat Scale: Hot

Thai Green Curry Paste (Kreung Gaeng Kiow Wahn)

This standard Thai green curry paste has dozens of uses; it is a must for green chicken curry. It can be added to any other curry preparations, be it Indian, Vietnamese, or Cambodian. Just adding one teaspoon of this paste will make other curry concoctions more flavorsome, more zesty, and more pungent. Heat this paste in a wok or skillet, add your favorite chopped meat, fish, or vegetables, cook for 20 to 30 minutes, and you have a wonderful Thai curry to serve over rice.

Ingredients

- 1 tablespoon coriander seeds

- 1 tablespoon cumin seeds

- 6 whole peppercorns

- 3 stalks lemongrass, bulb included, chopped

- 1/2 cup cilantro

- 1 2-inch piece of galangal or ginger, peeled

- 1 teaspoon lime zest

- 8 cloves garlic

- 4 shallots, coarsely chopped

- 12 green chiles such as serrano, stems removed, and halved

- 1/4 cup water

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon shrimp paste

Instructions

- Roast the coriander and cumin seeds for about 2 minutes in a dry skillet, and when they are cooled, grind to a fine powder in a spice mill.

- Combine all ingredients in a food processor or blender and puree until a fine paste is formed.

- Pour the paste into an airtight jar and refrigerate. It will keep in the refrigerator for about a month.

Yield: About 1 1/4 cups

Heat Scale: Hot

Lemongrass Curry

This recipe was collected in Cambodia in 1992 by Richard Sterling. Richard commented: “This is my personal all-purpose four cup curry which is based on extensive observation and many trials. To prepare a meal for one, pour 1/2 cup of this curry sauce into a shallow vessel or a wok. Add 1/2 cup of chopped meat or vegetables, bring to a medium boil and cook to the desired degree. Try it with frog legs, as the Cambodians do.”

Ingredients

- 1/3 cup sliced lemongrass, including the bulb

- 4 cloves garlic

- 1 teaspoon dried ground galangal

- 1 teaspoon ground turmeric

- 1 jalapeño chile, stem and seeds removed

- 3 shallots

- 3 1/2 cups coconut milk, recipe here

- 3 lime or lemon leaves

- Pinch of salt or shrimp paste

Directions

- In a food processor or blender, puree together the lemongrass, garlic, galangal, turmeric, jalapeño, and shallots.

- Bring the coconut milk to a boil and add the pureed ingredients, lime leaves, and salt, and boil gently, stirring constantly, for about 5 minutes. Reduce the heat to low and simmer, stirring often, for about 30 minutes, or until the lime leaves are tender and the sauce is creamy. Remove the leaves before serving.

Yield: 4 cups

Heat Scale: Medium

Laotian Catfish Curry

This curry recipe, collected by Richard Sterling in Laos, features the silky smooth paste typical of that cuisine. “Maceration of the curry paste ingredients is critical,” he observes. The ginger, or galangal, he says, “is used for both its culinary and mystical value; in the currency of the spirit world it represents gold.”

Ingredients

- 6 shallots, peeled

- 1 2-inch piece of ginger, peeled

- 3 small fresh red chiles, such as serranos, stems removed

- 5 cloves garlic

- 1 2-inch piece galangal, peeled

- 2 cups thick coconut milk, recipe

- 1 tomato, peeled and chopped

- 1 smalled eggplant, peeled and diced

- 1 pound catfish, cut into large chunks

- 1/2 pound green beans, cut into 1-inch sections

- 2 tablespoons minced cilantro

- 1 teaspoon fish sauce (nam pla)

- Water or fish stock, if needed

- Cilantro leaf for garnish

- Nigella seeds for garnish

Instructions

- In a food processor, combine the shallots, ginger, chiles, garlic, and galangal and puree to a smooth paste.

- Bring the coconut milk to a boil in a wok, add the paste, reduce the heat slightly, and cook, stirring occasionally, for about 5 minutes. Add the tomato and eggplant and cook for five more minutes.

- Add the catfish, beans, cilantro, and fish sauce, and cook over medium heat for ten minutes, or until the beans are tender. The curry should be quite liquid, so add some water or fish stock if necessary.

- Serve garnished with the green onion.

Yield: 4 servings

Heat Scale: Hot

Read more about curries in Dave’s comprehensive exploration of the subject, A World of Curries. You can pick up a copy his bookstore, here.