Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Curiosities of Food, 1859, by Peter Lund Simmonds.

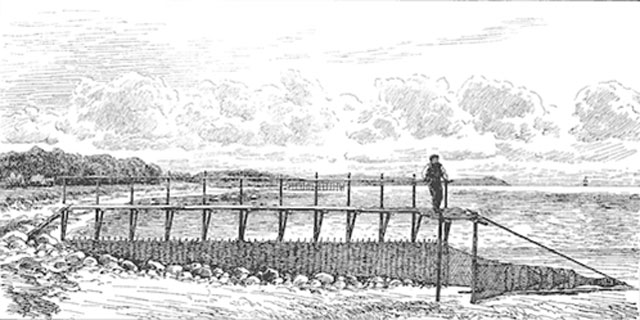

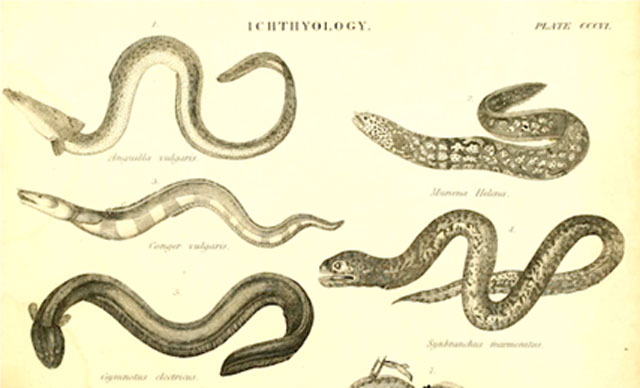

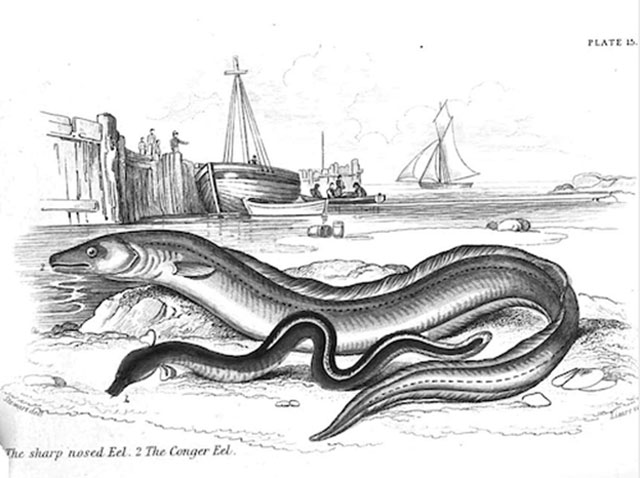

The regulation and management for the sale of eels seems to have formed a prominent feature in the old ordinances of the Fishmongers’ Company. There were artificial receptacles made for eels in our rivers, called Anguilonea, constructed with rows of poles that they might be more easily taken. The cruel custom of salting eels alive is mentioned by some old writers. The flesh of the eel (Anguilla vulgaris), being highly nutritious, is excellent as food, but is sometimes found too oily for weak stomachs. Eel pies and stewed eels cause a large demand in this metropolis, and some 70 or 80 cargoes, or about 700 tons a year, are brought over from Holland. The total consumption of this fish in England is estimated at 4,300 tons per annum.

Eels are very prolific. They are found in almost all parts of the world. An abundance of large eels of fine quality are caught in the rivers and harbours of New Brunswick. If a market should be found for this description of fish from North America, they could be furnished to an unlimited extent. My friend and correspondent, Mr. Perley, says, “In the calm and dark nights during August and September, the largest eels are taken in great numbers by the Micmac Indians and Acadian French, in the estuaries and lagoons, by torch – light, with the Indian spear. This mode of taking eels requires great quickness and dexterity, and a sharp eye. pursued with much spirit, as, besides the value of the eel, the mode of fishing is very exciting. In winter, eels bury themselves in the muddy parts of rivers, and their haunts, which are generally well known, are called eel grounds. The mud is thoroughly probed with a five-pronged iron spear, affixed to a long handle, and used through a hole in the ice. When the eels are all taken out of that part within reach of the spear, a fresh hole is cut, and the fishing goes on again upon new ground.’

It was by a mistake that the Jews abstained from eating eels. The prohibition is as follows:-‘ All that have not fins and scales, &c. , ye shall have in abomination .’- Lev. xi . , 10, 11, The Silurida, which have no scales, were held in abomination by the Egyptians. In describing one of them (the Schall) which he had found in the Nile, M. Sonnini, says — A fish without scales, with soft flesh, and living at the bottom of a muddy river, could not have been admitted into the dietetic system of the ancient Egyptians, whose priests were so scrupulously rigid in proscribing every aliment of unwholesome quality. Accordingly, all the different species of Siluri found in the Nile were forbidden .’ This then was probably one of the forbidden kinds, and this fact supports the opinion before ventured as to the origin of the custom. The rest of the prohibition was probably levelled against aquatic reptiles, which were generally looked upon as possessing poisonous qualities.